All About Development Permits

Development permits are required in almost every jurisdiction before a property owner can construct a new building or project beyond a single family home. Land divisions are a special form of development permit (please also see our information bulletins on Parcel Maps and Final Maps). Often, development permits are discretionary , meaning they can be denied or modified, instead of being approved if the City or County feels that this is necessary to protect the environment or the public health, safety, and welfare. Some development permits are ministerial , meaning that they will definitely be approved if prescribed development standards are met. Use Permits are a special form of a development permit that may or may not be considered appropriate for a particular location.

In any event, the process of obtaining approval of a development permit has become far more complicated than in the past. A development permit application is born out of your desire to use your land in a particular way. As an example, you may have purchased land that is properly zoned for an office building and you intend to construct an office for your own use, lease, or sale.

We begin our review of your idea with a meeting where we learn about your goals and what you know about your land. We do additional research, including a field review of the site, to make preliminary determinations about whether your idea will work, and what challenges might be faced in the process. Generally our preliminary review includes consideration in three major, equally important areas affecting land use:

1. Regulations and Rules: Is the use compatible with the General Plan, Zoning Ordinance, and other applicable rules? Sometimes meetings with agency officials or even a formal pre-application process might be needed to fully understand how rules will be interpreted and applied.

2. Site Constraints and Capabilities: Is your land physically suited for the use and development intended? Does the particular City or County mandate protection of certain resources like steep slopes, large trees, or stream zones? Is there an available method of sewage disposal, water, and an availability of other utilities and services?

3. Political Realities: Is the particular City or County inclined to approve your proposed use in this location? Is it likely to be incompatible with the neighborhood or otherwise spawn objections to the point of persuading the City Council or Board of Supervisors to deny it?

Realistically, most built projects, beyond a vacant lot land division, require that you assemble a planning team to prepare an application meeting prevailing City or County standards. Your design team usually consists of planning and civil engineering services from our firm, building design by an architect, and landscaping design by a landscape architect.

Most jurisdictions require the preparation of various technical studies to fully disclose site constraints, so that their environmental studies and public review can be completed. Typical technical studies include a Phase 1 Environmental Report to disclose any suspected hazardous materials, a Preliminary Soils Report to disclose any obvious soil stability problems, a Biological Inventory to disclose any protected plants, animals or protected resources, an Archaeological Report to disclose any pre-historic (Native American) or historic cultural resources, and other similar studies.

Your team will assist you in preparing a development permit application by preparing all of the materials requested by the City or County. Typical application materials include a detailed site plan, a preliminary grading plan, a landscaping plan, building design (including materials and colors), a lighting plan, and a signage plan.

This information is submitted to the City or County with a processing fee designed to cover the average actual cost of public review and processing. Sometimes the City or County will require a deposit and will bill you as needed toward the actual cost. Once submitted, the City or County has 30 days to determine wether the application is complete. If not, they can stop processing until missing materials have been submitted.

With the exception of a few minor projects, the City/County planning staff will complete an environmental initial study under the requirements of the California Environment Quality Act (CEQA). This study will objectively examine the potential adverse environmental impacts of your project and suggest mitigation (offsetting) measures. For example, if your property includes a stream, the City/County might require that development be setback and that the stream area be fenced during construction to protect it. Traffic impacts might be mitigated by the payment of development fees and/or the construction of selected traffic improvements.

For larger projects, an environmental impact report (EIR) might be required. For smaller projects, it is more likely that a "mitigated negative declaration" will be used instead. This document is more informal and faster than an EIR. The City/County always notifies interested agencies and the public that it intends to take a particular environmental action. The public then has a chance to request a higher level of study or to request additional mitigation measures.

Many jurisdictions hold informal staff meetings on an application to discuss mitigation measures, conditions of approval, public improvements needed, and project design. Such committees are often called development review committees, advisory committees, or design review committees. Such meetings usually prove useful in providing clearer communication between the City/County and you as the applicant. Often minor project changes are made at this stage, as requested by the committee, and quite often these changes actually improve the project.

Finally, the City or County will hold one or more public hearings to make a decision on your permit. Most decisions are made at the Planning Commission level, but some projects need final approval from the City Council or Board of Supervisors. Prior to the hearing, formal notice is mailed to all property owners within 300' (or 500' in some cases) of your property. Neighbor notices must be sent at least 10 days prior to the hearing.

Sometimes, one or more neighbors will object to your project. Sometimes, neighbors are alarmed that they have only received 10 days notice before the hearing. For these reasons, it is sometimes worthwhile to do a voluntary neighborhood public relations or information program. There are pros and cons to such early neighborhood contact. The Planning Commission will greatly appreciate such an effort. Often concerns about a project can be defused in advance with minor changes and assurances for the neighbors' benefit. On the other hand, sometimes early contact provides more time for neighborhood opposition to be organized and directed.

The Planning Commission or City Council or Supervisors will weigh neighborhood testimony to determine whether it has validity. They will work with their staff to separate legitimate concerns from concerns with little or no basis. They will strive to consider project changes or mitigation measures that will help offset legitimate public concerns. As an example, they might limit the operating hours of a proposed store to provide more peaceful evenings to the nearby neighbors.

Once a decision is made at the Planning Commission level, it may be appealed by any interested person. If you as the applicant feel that the conditions of approval are too severe, you might elect to appeal to the City Council or Board of Supervisors to have the condition removed. By the same token, those neighbors that objected to your project might also appeal. An appeal hearing is usually a brand new hearing, where all aspects of the project and approval can be reopened and reconsidered.

Decisions of the City Council or Board of Supervisors may be challenged by filing a lawsuit. In some instances, the initiative process is also available to the public. With the initiative process, opponents prepare a voter initiative and gather signatures to put the measure to a vote of the people. The people, through the initiative process, have the same power as the City Council or Board of Supervisors.

Lawsuits are almost always filed within 30 days of the final action on the project, when the "Notice of Determination" under CEQA is filed. Almost all such lawsuits are filed on the basis of alleged flaws in the environmental review process. Most jurisdictions now require the applicant to be responsible for the cost of defending a lawsuit against the City or County. You may be required to sign an indemnification agreement guaranteeing the cost of defending the City or County's decision.

Once you survive the approval process, then you basically have a "contract" with the City or County. In other words, as long as you satisfy that long list of approval conditions and mitigation measures within the approval time period (usually 2 years), you can build your project. Extensions of time for the project approval are usually possible. The major expense and time consuming points after approval, are for the preparation of civil engineering grading and drainage plans and preparation of full architectural building plans. These plans, called working drawings , need to be reviewed and approved by the City or County before grading and building permits are issued. Often, approval by electrical and water providers are also needed.

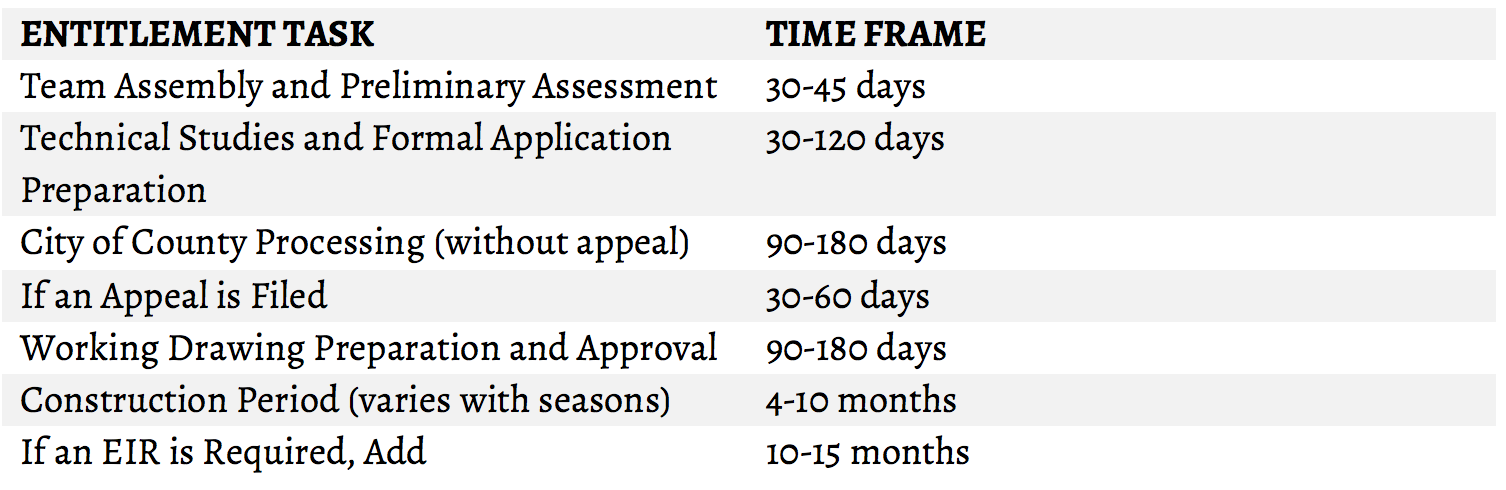

The time frames for the entitlement process vary considerably, depending on the jurisdiction, the project, the neighborhood, and the work load of team consultants.

The following time ranges are typical:

Contact Andy Cassano of our office for additional information.